In my new book, Cultural Competency for the Health Professions,

http://www.jblearning.com/catalog/9781449672126/ there are stories which address the issues associated with the rapid demographic changes taking place in the United States and the approaches that health care professionals must take in order to provide culturally competent care to their patients/customers from diverse backgrounds. These stories, known as case studies, focus on many health professionals, but the one below is of particular interest to N.I.C.E. since the issue is about natural hair. To read more of these stories/case studies and other interesting info., including an interview that I conduct with Dr. Donna Shalala, former Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services and current President of the University of Miami, which is Chapter 10, check out the book. I think you will find it an interesting read. I would love to read your comments/thoughts. The book is also accompanied by an interactive website!

A N.I.C.E. excerpt from Cultural Competency for the Health Professions (pgs. 120-122)

A Medical Assistant calls in her patient, an

African American woman to take her blood pressure, weight and other vitals before she sees the Physician. The Medical Assistant notes that the African

American woman has extremely long, thick hair in a style known as locks. As the patient stands on the scale, the

Medical Assistant asks her how much does she think she would weigh without her

hair. The African American woman is

rather surprised and responds by stating that she doesn’t understand. She looks

at the Medical Assistant who has short blonde hair and asks “Do you mean if my

hair was short? I don’t understand your

question.” “No", the Medical Assistant replies.

I mean if you remove your hair.” The

patient is quite offended as her hair can not be removed as it is her own and

explains to the Medical Assistant that her question was inappropriate and

inaccurate and asks if she could just record her weight and move on to the

blood pressure. The Medical Assistant

looks at her with trepidation, still suspect about her hair and proceeds by

asking the patient to roll up her sleeves so that she can apply the blood pressure

cuff. The patient is visibly offended,

based on her expression but receives no apology from the Assistant. After

completing the blood pressure check, the Medical Assistant states to the

patient that her blood pressure is very high.

“You may want to consider cutting out the soul food.” The patient replies curtly, “I am a

vegetarian and I do not eat soul food.”

The Medical Assistant leaves curtly indicating that the doctor will be

right in. The patient seriously

considers leaving as she waits for the Doctor to see her and she has been

offended twice by the same Health Professional without an apology in either

instance .

Comments:

In this case, a cultural insult has been

levied against the African American woman, leading her to feel slighted. Often times, women of African descent are

sensitive about their hair because it is a critical aspect of their culture

based on historical implications. When

the atrocious slave trade ensued, most Black people were brought to the

Americas, against their will, primarily from the West Coast of Africa. This process, known as chattel slavery, was

brutal, inhumane and included removal of the identity of the individuals who

were enslaved, hence cultural genocide. On the ships during the unsavory

journey to the New World, slaves who spoke the same language or had the same

markings of scarification were separated.

They were also not permitted to communicate through drumming which was

another form of language for them. While on the continent of Africa, specific hairstyles were used to

identify their geographic regions.

For example, young girls

partially shaved their heads as an outward symbol that they were courting in

Senegal (Byrd and Tharps, 2002). The

Karamo people of New Jersey were recognized for their unique coiffure—a shaved

head with The Karamo people of Nigeria, for example, were recognized for their

unique coiffure—a shaved head with a single tuft of hair left on top (Byrd and

Tharps). Likewise, widowed women would

stop attending to their hair during their period of mourning so they would not

look attractive to other men. As far as

community leaders were concerned, they donned elaborate hairstyles. The royalty

would often wear a hat or headpiece, as a symbol of their stature. Africans from the Mende,

Wolof, Yoruba, and Mandingo tribes, transported to the “New World” on slave

ships, often communicated age, marital status, ethnic identity, religion,

wealth, and rank in the community through their ornate hairstyles. The Middle Passage (the name used to

describe the transport of slaves from Africa to the new world on slave ships

across the Atlantic Ocean) and beyond, resulted in removing this rich hair

heritage for African people brought in as slaves now known as African Americans

and those who were brought to the Caribbean, Central and South America. Africans were no longer

able to maintain elaborate hairstyles without their combs and herbal treatments

used in Africa. Slaves relied on bacon grease, butter and kerosene as hair

conditioners and cleaners. Africans from the Mende, Wolof, Yoruba, and Mandingo

tribes, transported to the “New World” on slave ships, often communicated age,

marital status, ethnic identity, religion, wealth, and rank in the community

through their ornate hairstyles. From Ancient Egypt to West and East Africa,

the Hair of African people was (and still is) an Adornment: Both valued and

appreciated. Unfortunately, Black hair

was referred to as “wool” by the slave holders (Ivey, 2006); Whites looked upon

blacks that later learned to style their hair like white woman as “well adjusted. “Good” hair became a requirement to enter

schools, churches, social groups and business scenarios. In 1880 the hot comb was

invented by the French. It was heated

and used to straighten “kinky” hair. As Time progressed the hair of Black

People was ridiculed and despised and referred to as “Buckwheat”, Kinky,

Nappy, Bird feathers and “Pickanninny

(refers to black children of slaves and later African Americans, or a

caricature of them which is widely considered racist) (Pilgrim, 2008). Rags/Scarves were placed

over the heads of black women in books, films and statuettes and they were

referred to as Mammies on television and other forms of the media.

This painful history has caused many

women of African descent to be extremely conscious and sensitive about their

hair and as a consequence songs and poems have been written to help them to

deal with this aspect of their lives.

The famous modern day singer India Airie, after shaving her head

completely in an effort to respond to the cultural indignation of her hair

experiences throughout her career, wrote the following:

“As a Black American woman, a lot of your

integrity is dictated by how you wear your hair,” she explains. “The concept

for the song was sparked when I decided to cut my locks, and all the different

attitudes people had about it. This is my hair – and it’s my life. I’ll choose

how I express myself.” (excerpted from the contemporary song, “I Am Not My Hair”).

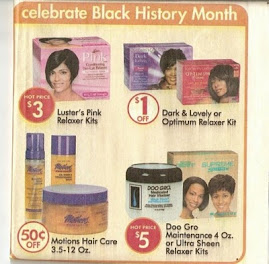

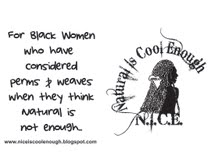

Many African American women have turned to weaves, extensions and other

remedies to address the hair issue. Also, others have turned to natural

hairstyles.

It is a fact that the

natural hairstyles worn by African Ancestors and some Black women today

enabled/enable them to avoid scalp burns, hair breakage, and hair loss that

often result from using harsh products to straighten their hair. As such, some

Black women of every generation have chosen to wear their hair naturally

regardless of trends.

Hence, natural

hairstyles, such as locks, repeatedly resurface in the mainstream and are worn

with extreme pride.

Therefore, those in

healthcare, in approaching the notion of cultural competence as it relates to

women of African descent, must consider this, as an example of an important

cultural concept.

Specifically the

importance of understanding the significance of an African American women’s

hair and how to discuss it is a pertinent cultural concept which can lead to a

serious cultural insult if not handled correctly.

Sources:

Byrd, A. and Tharps, L. (2002). Hair Story: Untangling the roots of black

hair in America. New York, St. Martin’s Griffin.

Ivey, K. (2006). Combining the

history of Black hair.

Sun Sentinel, February

21.

Pilgrim, D.

The picanniny caricature. Ferris

State University Museum of Racist Memorabilia.

Retrieved June 6, 2011, from

http://www.ferris.edu/jimcrow/picaninny.